Over the last 10 seasons, the NBA has evolved. The game of basketball is always evolving, but in 2004, the NBA made a couple of seemingly small rule changes that have had an enormous impact on how teams were allowed to defend. After years of some excessively physical defense, stagnant, isolation-heavy offenses and a steady decline in pace and points scored, the league made an effort to speed up the game and allow for skill to better compete with strength.

As the game was beginning this period of repaid evolution, the way that fans experience and understand the game has undergone a period of rapid change as well. It is amazing to think that just 30 years ago, NBA playoff games were on tape delay. Today we have access to every single game in every market, an abundance of archive footage, and an ever growing amount of sports statistics and analysis. Fans can learn their favorite team’s plays, nomenclature, and defensive strategies at the click of a mouse. Also, they can look up how far and how fast their favorite player ran during a particular game — and the amount of information that fans have access to is growing. Whether you prefer the modern era of basketball or any previous era of basketball, with the amount of resources at our disposal, this is certainly the golden era of NBA fandom.

But despite the availability of unique and insightful analysis, the collective conscience of NBA fans is still most strongly influenced by a small number of very widely influential talking heads. Since nationally televised games are distributed on two major networks, TNT and ESPN, their talking heads have used the loudest microphone available to drill several myths about NBA basketball into the collective conscience of basketball fans. These myths have taken on a life of their own and have shaped the conversation and the way most fans view the game. While there is plenty of area for disagreement amongst great basketball minds, there is little room for disagreement about certain aspects of the game. I’ve broken down 5 of the most common myths in the NBA fan-o-sphere.

Myth #1: You live by the 3, you die by the 3

Anybody who attended a summer camp or played high school basketball had axioms drilled into their head about basic fundamental principles. “Live by the 3, die by the 3” is certainly one of those axioms. While the saying might be true for lower levels of basketball where 3-point shots are less predictable and less efficient, this is not the case in the NBA.

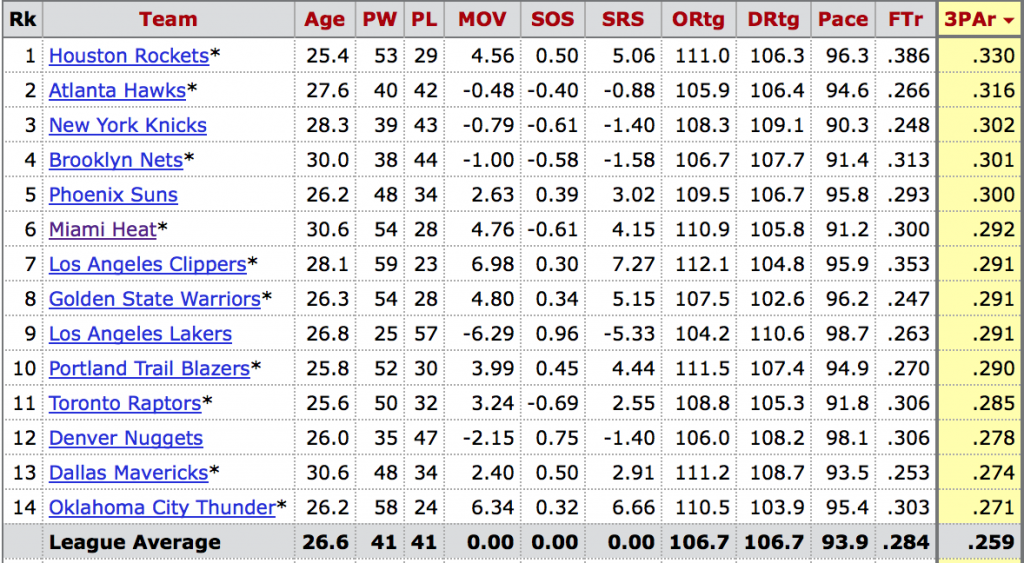

Most casual NBA fans understand that it has evolved into a much more 3-dependent league. Teams averaged more 3-point FGA’s in the 2014 season than any season prior, and the increased dependency on 3’s is remarkably steady. Last season, of the 14 teams that took above league average 3-point FGA’s, 10 were playoff teams.

There are two main reasons why the NBA is trending this way. The first is that 3-point FGA yield more points per shot than most 2 point FGA. This is basketball analytics 101. The secondary reason for the trend toward increased 3-point attempts is because it spaces the floor. One of the rule changes in the early 2000’s states that a defender can only stand in the restricted area for three seconds at a time, unless he is within arm’s length of the player he is defending. By utilizing players around the perimeter, defenders are unable to stand and protect the basket. It has a chicken and egg effect whereby taking more threes opens up the lane to the basket — and attacking the basket opens up shooters on the perimeter.

But what most people think when they say “live by the 3, die by the 3” is that the 3-point shot can be fickle. Sometimes you hit 5 in a row. Sometimes you miss 5 in a row. Teams should look for more efficient shots and shouldn’t settle for shots that are so inconstant. The flaw in this logic is that all shots are fickle. It is a make-or-miss league. Teams, however, are very good at getting shots that they want. And statistics have shown that the 3-point shot is exceptional in it’s expected value.

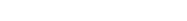

Myth #2: Power forwards and centers, like Bosh and Howard, should post-up more

It started a few seasons ago when Shaquille O’Neal, one of the best post up players of all-time, started criticizing Howard for his pick-and-roll style of play. Shaq would remind anyone who would listen of the times he would dominate games from the post and never “settled” for the pick-and-roll. The meme caught on, and Howard has been taken to task by fans for his lack of post dominance. O’Neal is right that Howard is not a very productive post-up option. Through the midway point of the season last year, Howard averaged just 0.75 points per shot on post-up plays while 50% of his FGA’s came from those kinds of plays. The irony, however, is that Howard is one of the best pick-and-roll players in the game. Through that same stretch, Howard averaged an amazing 1.26 points per shot attempt out of them, but took less than 8% of his FGA’s in those situations.

As polarizing as Howard is, perhaps no big man is more polarizing amongst fans than Chris Bosh. The Miami Heat big man averaged just 3.2 “close touches” per game last season, good for 60th in the league. That ranked behind players like Jordan Hill and Kosta Koufos, despite playing significantly more minutes than both. Critics of Bosh often cite him for being soft and afraid to bang inside like power forwards should. But this is a very antiquated way of looking at the power forward position. Bosh scored .52 points per half court touch last season, which is 17th best amongst players who average the same amount of close touches or more. In short, Bosh is scoring more efficiently from his spots on the court than reputable post players and tough guys, like Nene and Zach Randolph.

Posting-up can be an extremely effective way to score points and open up the offense. But it isn’t the only way. Bosh was able to ignore the “noise” of analysts like Shaq, and both he and the Heat were better for it. Howard should learn from Bosh and utilize the method of scoring that fits his skill set best. He should work hard to improve his footwork and touch in the post, but he has a lethal weapon in his ability to finish on the pick-and-roll that should take up far more than 8% of his FGA’s.

Myth #3: Defense wins championships

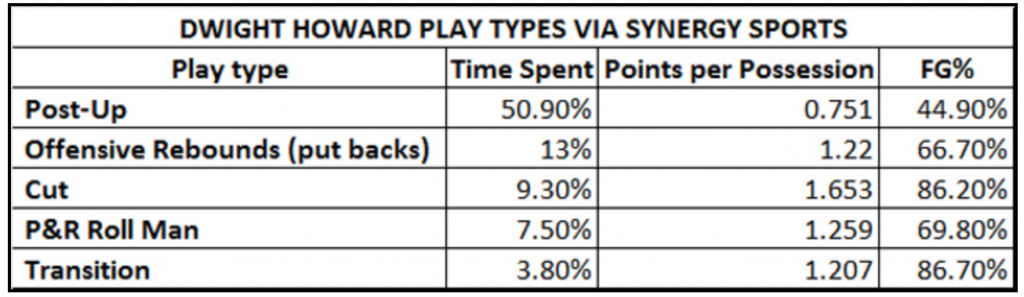

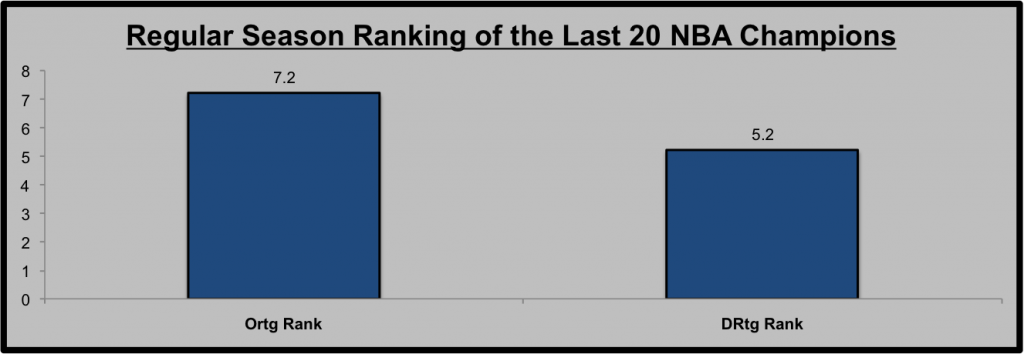

Another axiom straight from summer basketball camp and for the most part, an accurate one. Of the last 20 NBA champions, 18 were in the top 10 in DRtg. Similarly, 16 of the last 20 were in the top 10 in ORtg. Only 5 times has the league leader in DRtg won the title, while the league leader in ORtg has won it twice. The average ORtg rank is 7.2, while the average DRtg is 5.2. What this means is that it takes more than just defense to win championships. A more accurate axiom would be defense and offense wins championships — but that becomes less of an axiom and more just simple logic.

Over the last 20 years, NBA champions are on average the 7th most efficient Offense and 5th most efficient Defense

Consider the 2014 NBA finals. The Spurs allowed 104.8 points per 100 possessions during that series against Miami, a number that is almost perfectly average compared to the last 20 NBA finals champions. However, they had a historic 60.4% effective field-goal percentage. To quote Pat Riley, the 2014 Spurs were a “buzzsaw” on offense. It’s important to be great on both sides of the court, but sometimes offense wins championships.

Myth #4: There is a “right way” to play the game

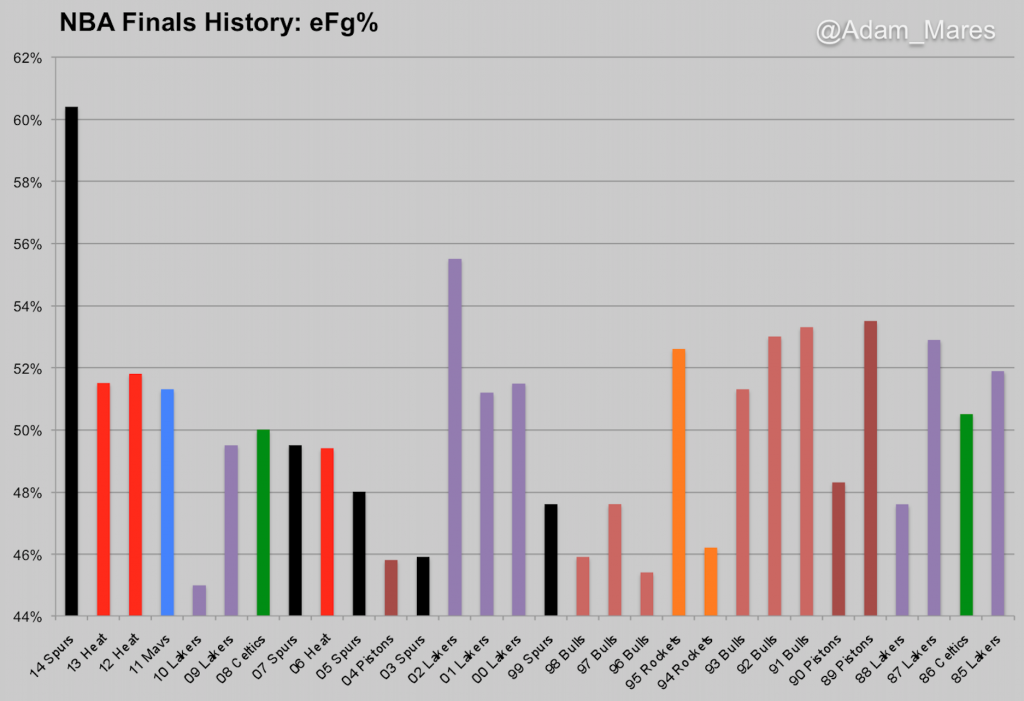

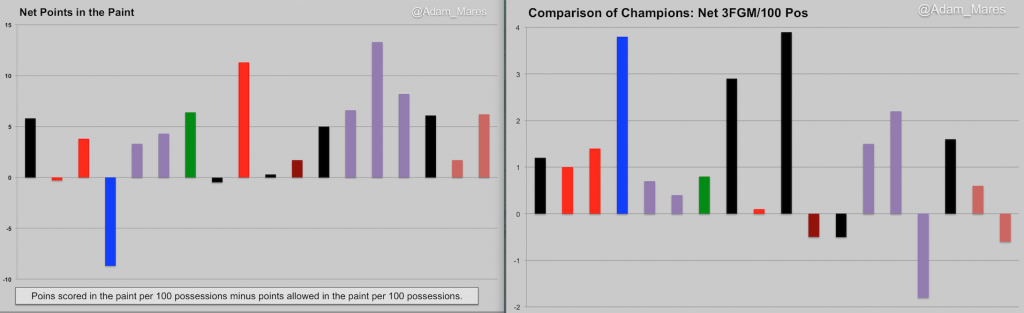

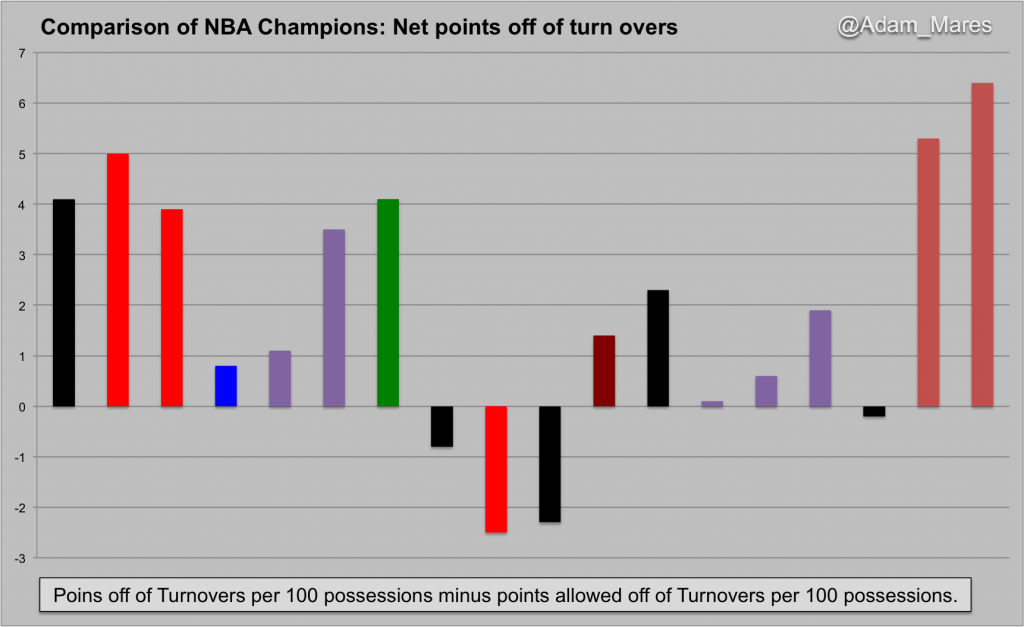

To say that there is a “right way” to play the game would imply that only one style of basketball prevails — but if we look at the last 20 years of NBA champions we see incredible variation. The 1997 and 1998 Chicago Bulls outscored their opponents by over 5 points per 100 possessions on points off of turnovers. Other teams, like the 2005 Spurs and the 2006 Heat, actually lost the points off of turnover battle.

The most consistent statistical identity for NBA champions is that they own points in the paint. Yet even the 2011 Dallas Mavericks were outscored in the paint during the finals by an astounding 8.7 points per 100 possessions. They made up for their shortcoming in the paint, though, by making nearly 4 more 3-point field goals per 100 possessions.

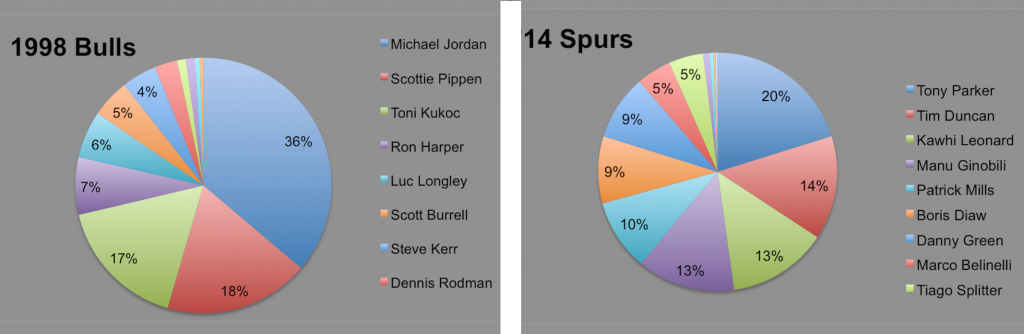

The “right way” to play often infers a certain level of teamwork and unselfishness, which is certainly a pillar of successful basketball. Teams like the 2014 Spurs and the 1980’s Celtics and Lakers have won championships when the team’s FGA distribution is spread fairly even among it’s top 7 or 8 players. But teams have also had success when one player attempts a larger percentage of their teams FGA, like the 1990’s Bulls and 2000’s Lakers. The “right way” to play seems to change year to year.

Myth #5: NBA success is black and white

Thumbing through the archives of statistical data for the last 30+ NBA champions, one thing jumped out the most: there is a thin line between winning and losing. Champions seem inevitable when you look back at history. The 1980’s Lakers seemed destined to win 5 championships, while Chicago in the 1990’s seemed destined to three-peat, and then three-peat again. But as you thumb through the archive footage and dive into the advanced stats, you see a much different reality. The battle margin is often much more thin than we like to admit.

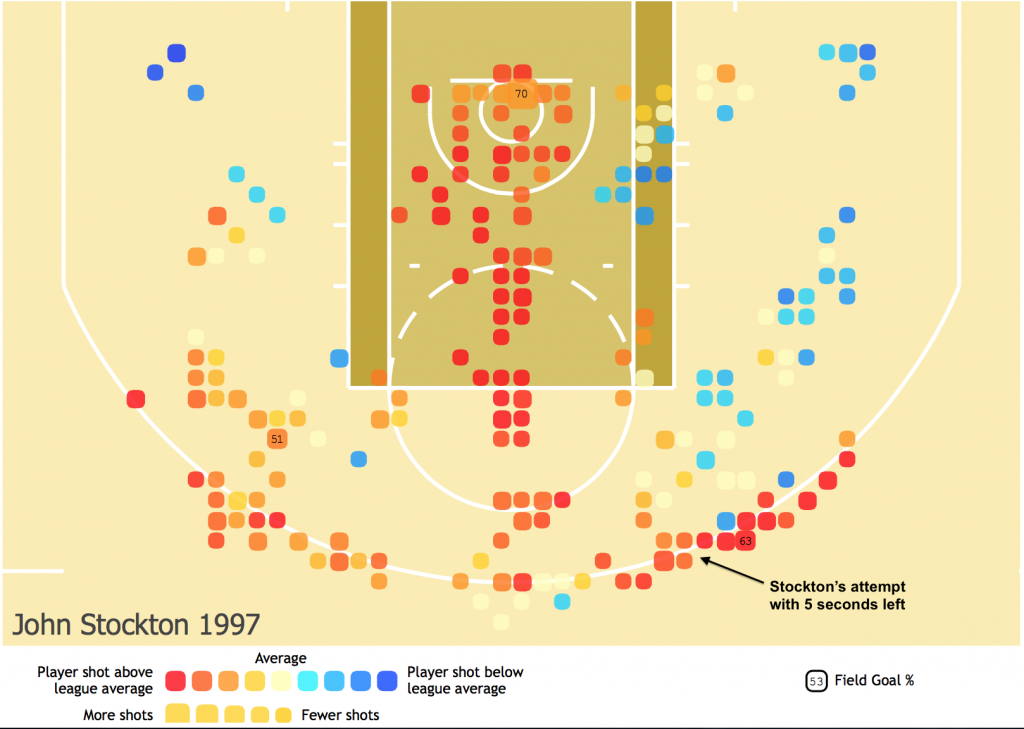

In the last 30 seasons, 5 NBA champions have been outscored in the finals and still won. The 1988 Lakers were outscored by 18 points overall and won game 7 by just 3 points, a game in which Isaiah Thomas played through injury and sat most of the 2nd half. In 1998, Michael Jordan hit what has become perhaps his most famous shot — a free throw line jumper over Byron Russell to give the Bulls a 1 point lead with 5.2 seconds left. It was a perfect ending that could have been ruined by John Stockton, who got a fairly open look from his favorite spots on the court.

The 2000 Lakers were outscored by both the Portland Trailblazers and Indiana Pacers, yet were able to win both series and secure the first of three straight championships. They famously rallied back from a 13-point, 4th quarter deficit in the conference finals — in a game that saw both Scottie Pippen and Arvydas Sabonis foul out. Most recently, the Heat rallied back from an improbable 5-point deficit with just 30 seconds remaining to force Game 7 against the Spurs in 2013. None of these champions should be considered “lucky” — they each earned their place in history. But it would be a mistake to view the outcome of any season as inevitable or to think that the only stat that matters is championship rings.

It is often said that history is written by the winners. For most NBA fans, history is written for the winners, but there is a broader story to tell. The line between winning and losing is often razor thin — who wins and who loses is black and white — but much of NBA basketball is played in the gray, and we are all very lucky for it.