An interesting development in the past month or so — since the 2014 NBA draft in which Andrew Wiggins, Aaron Gordon, and Marcus Smart were some of the hottest commodities — has been the growth of rebuilding teams who are focusing primarily on athleticism and defense from their new young talent.

The Orlando Magic (who have put their stock into Victor Oladipo, Elfrid Payton, and Aaron Gordon, all very good defenders and athletes and poor shooters), are the most clear example of a team hoping that sheer youth and athleticism can outweigh skills like shooting and floor spacing.

The Boston Celtics, though (with all their metaphorical chips bet on Marcus Smart, Avery Bradley, and the raw James Young), and perhaps the Utah Jazz and Minnesota Timberwolves also fit the bill, depending on how well Dante Exum and Wiggins turn out to be as 3-point marksmen.

This is interesting because these teams are all choosing to more or less eschew shooting at a time when 3-point shooting and floor spacing have an all-time high value.

There are several valid rationales for these decisions, and the consequences of each team’s decisions will be fascinating to watch. When these players were drafted, they were picked for one of two different reasons:

- They were theoretically the best players available at their draft slot, or in a potential trade, independent of skillset fitting the team (see: Wiggins, Smart, Young, Exum).

- They fit a particular team identity (Gordon, Payton).

Whether or not the Celtics, Jazz, or Wolves manage to leverage the young athelticism-and-dearth-of-shooting into functional teams is still up for grabs, but they’re not particularly constructed off of an attempt to build a team around their skillset, so much as they’re constructed off of a clear necessity for raw talent.

The Magic are probably the more interesting case, then, because they’re a team who have drafted their players around an understanding that these are players who can’t particularly shoot.

The decision to build around these players similarly stems from a few different ideologies. Either the team believes that its drafted players can learn how to shoot, or the Magic decided that they doesn’t ultimately care whether or not the team can shoot. Both have some interesting implications.

First and foremost, its worth addressing the idea that a team should always draft the most athletic or talented player, because that player can learn how to shoot. History has indicated that that’s not necessarily the case.

To demonstrate, I went through all the DraftExpress profiles of players drafted between 2010 (players who have had four years in the NBA to improve their shot) and 2005 (when the profiles no longer include NCAA data), and I recorded the shooting statistics for all the players for whom DraftExpress had determined that their shot could, and should, improve¹.

The sample of such players was surprisingly small, roughly 40 players over those years, and even fewer of those players had shot a large enough volume of 3’s for their career to have a significant sample. Only 11 of the 39 players had shot more than 850 3’s, and since it takes 750 3’s for a shooter’s ability to “stabilize,” that was a problem.

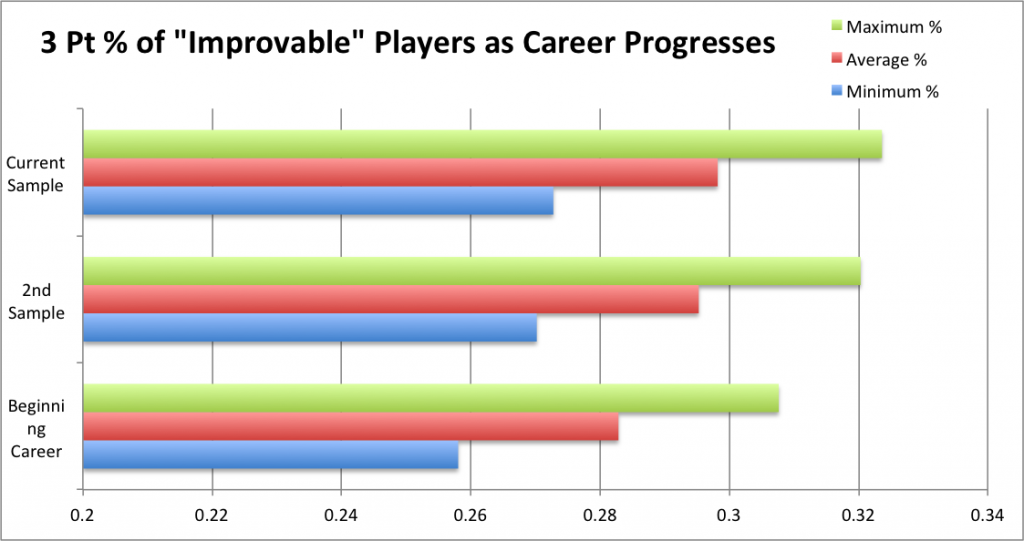

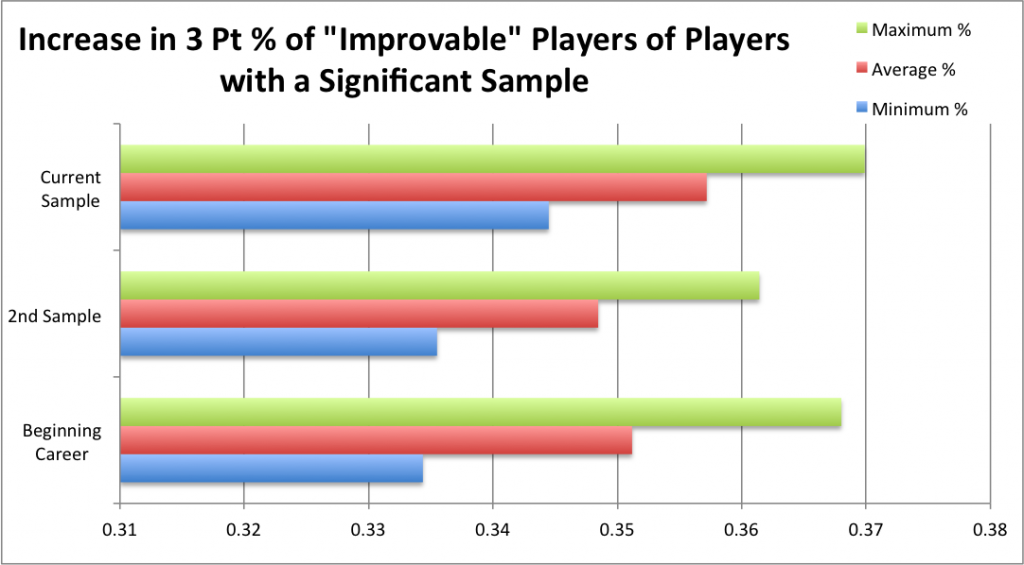

Nonetheless, by the standard T-test, the improvement in shooting for the entire sample is statistically significant with a 90% confidence (though, not necessarily with a 94% confidence or greater, which is important to mention).

To demonstrate improvement, I took three samples from each player: the first 750 3’s of their career, the second 750 (or, in most cases, the span from 300 shots or so to 1000 or their max), and the last 750. In the case of fewer than 1000 3’s (i.e. almost everyone), I considered the 2nd and current samples to be identical.

As well, the improvement over the sample of 11 players with a significant number of shots is significant at all confidence levels.

Still, significance only means that the increases from sample to sample aren’t entirely a function of sample error, and so the findings are still limited in accuracy by all the noise involved in shooting percentages, particularly the relatively small sample of shots. As well, this data isn’t on all player’s ability to improve their shot, just on the players who were previously deigned to be able to improve their shot.

There are a few very, very telling pieces of information to be gleaned, though.

First, there were only three players on the list who came into the league shooting a below-average percentage who are now shooting above league average, over at least a 300 shot sample: DeMarre Carroll, Quincy Pondexter, and LeBron James.

Meaning, for all players since 2003 for whom “jumpshot improvement” was an important part of buying into their game, LeBron is the only person who has actually gone from below league average to above league average in a truly significant sample.

That’s not to say that there aren’t players who have improved their jumpshot. There certainly are. You can see, in both graphs, a steady (if small) improvement.

Consider, though, that every player who turned into a league average 3-point shooter already started their NBA careers as an above average shooter. If players can improve their jumpshot, they seem to do it between their last year in college and their first year in the NBA.

I mean, the maximum possible shooting average, accounting for all possible error, among all 40 players in the sample at their peak in shooting, is still way below league average. Players who are supposed to learn how to shoot may improve, but they also generally stay bad.

Forgive me, but I don’t think anyone in this draft class is LeBron.

So, if the Magic are really betting on Gordon or Payton learning to shoot, they’d better hope that at least one of them comes in shooting at around league average next year.

If they are not hoping that either player learns a jumpshot, though, there’s some questions to be asked: in a league built on 3-point shooting, could Orlando survive? What would that team look like? Is that a smart move?

Lets consider the Magic’s most likely youth-heavy bench lineup: Elfrid Payton – Victor Oladipo – Tobias Harris – Aaron Gordon.

Of those players, though, no one is an above average 3-point shooter. Let’s, for the sake of argument, say that Oladipo become a roughly league average 3-point shooter (his 32.7% accuracy could certainly get there on his way to his first 750 shots). Frye, too, could be the center in the lineup, giving them an elite big man floor spacer.

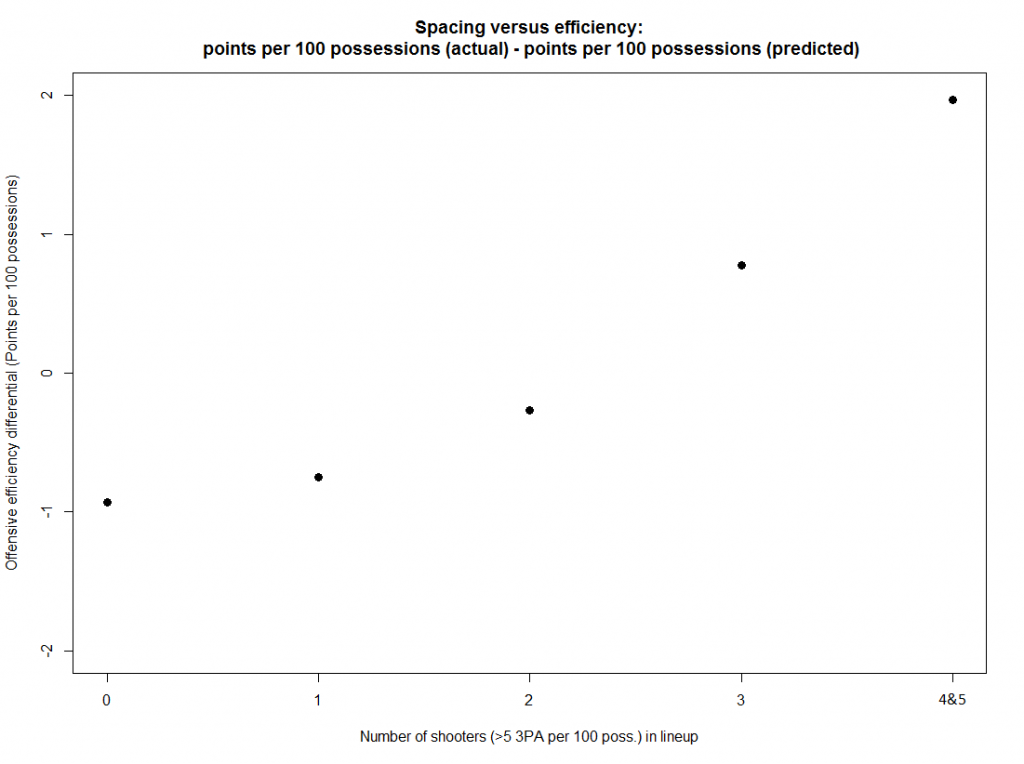

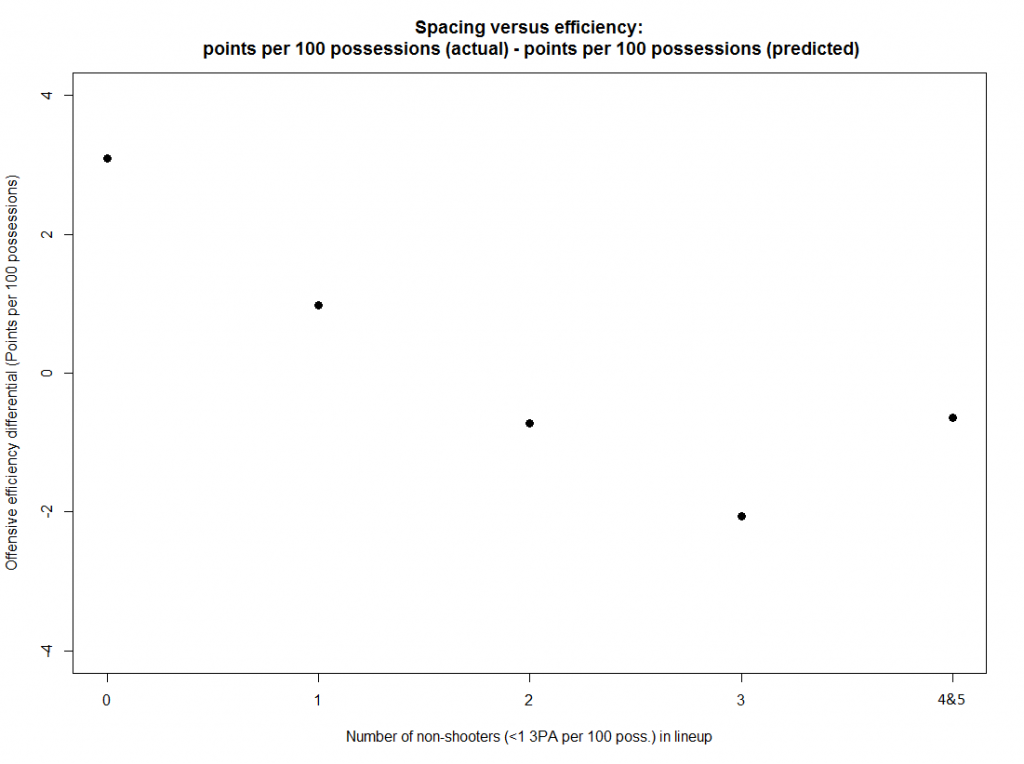

The combination of having few shooters (and conversely many non-shooters) and only one true “stretch” shooter, results in the Magic having to rely on youth who will hurt their offense, making it, on average, roughly 1-2 points per 100 possession worse than it might be otherwise².

That’s a big drop for a team already struggling with simply a limited amount of talent.

That limitation on Orlando’s offense could be potentially significant, but in the same lineup with only one stretch shooter and two league average shooters, there could be easily four elite defenders in that lineup, and Frye isn’t exactly a disaster either.

The result could be, in a few years, a team with a Memphis-style limited offense and stifling defense.

So far I’ve presented Orlando’s embracing of young talent that can’t shoot as a bad thing, but look: if Orlando can really defend at a top five or better level consistently, then it doesn’t matter what their offense is like unless they’re historically awful. Top five defenses are almost guaranteed playoff berths as of the last 15 years.

So, in the case that Orlando has been picking its talent carefully and for the particular aim of improving defense, and with little concern for shooting, it could very well turn out that Orlando has done itself a massive favor by putting together a more variable roster, but in particular one with a very specific aim: being elite at athleticism and defense.

Beyond the benefits to having a clearly worked out identity while rebuilding, teams are always better when they embrace being elite at a few things in particular.

Orlando choosing to be elite defensively and athletically, while eschewing any other concern, is actually much better for them in the long run than the Jazz or Wolves’ plans of building with a hope that they might be fairly good at just a few different things.

Look, the Jazz and Wolves could very well end up being much better from the sheer talent disparity between the teams. The Magic, too, could end up being three-point bombers for the next few years. They could roll out a starting lineup of Oladipo-Fournier-Harkless-Frye-Vucevic next season that could absolutely bomb from 3.

Still, that the Magic seem to be embracing a movement that primarily involves youth and defense is pretty much undeniable, and in so doing, they’re very clearly limiting their offense, while embracing an identity and skillset that still sets them up to be elite enough at a few things to differentiate them from the rest of the league.

At this point in the Magic’s rebuild, that’s a nice direction for Orlando to have, and it will be interesting to see in what direction they go more earnestly in future seasons.

¹I also included some players from earlier who were obvious candidates (LeBron and Dwyane Wade, mainly), and found other instances of sources calling the players’ jumpshots improvable, to ensure that the reputation was legitimate.

More problematic was whether or not each player’s profile contained sufficient optimism on their need to, or ability to, improve their jumpshot. I was looking for instances of “his mechanics are solid, and with some time could be a good shooter,” and less instances of “he has a great shot,” or, “he really needs to spend a lot of time in the gym to improve.”

However, there was a lot of grey area between those instances. I simply attempted to use my best judgment.

²These articles from GotBuckets and Hickory-High.com are particularly illuminating with regards to the effect of having a certain number of shooters on the floor at any given time.