Since Dean Oliver first published Basketball on Paper in 2004 (and probably before), basketball analysts have been pushing the belief that a team’s offense should be built around shooting three pointers and taking shots at the rim — the two most efficient shots in basketball by a wide margin.

That philosophy has on a macro level been proven true, repeatedly, but none of more prominent stature have sought to prove this principle than Daryl Morey, figurehead of the basketball analytics movement. He has built the Houston Rockets, and in some ways more tellingly, the Houston D-League affiliate the Rio Grande Vipers, to be 3-point shooting, layup machines.

Using this extreme policy, Morey has repeatedly built some of the most potent offenses in the league. There’s a wrinkle, though. The Rockets have not fared particularly well in the playoffs at any point in Morey’s tenure.

In this case, the Rockets have failed to leverage their excellent offense to greater postseason success not because of the way the offense is structured, but because of the lack of defense on all Rockets teams in question.

It did get me thinking, though: is there a potential circumstance in which a team should not be focusing all its efforts into three point shooting and shooting at the rim? Or, is there an analytics argument against basing a team entirely on three point shooting and shooting at the rim for long term success?

There is, as it turns out, and so let me preface is by making a few statements: First, it’s been long understood that defense does indeed win championships, as the cliché goes.

Only one team has won the championship in the last 25 years without being in the top 8 in defense for the season: the ’01 Lakers. Almost 10 teams have won in that span without even being in the top 8 on offense.

It’s almost impossible to even get to the finals without playing a top-5 defensive team.

Second, in long term team building, the goal has to be to win championships. Always.

So, two fundamental things need to be true of a team for it to be a smart way to build a team: they need to be sniffing the top 5 in defensive efficiency, and they need to have an offense that will break down the best defenses. The key to the best defenses, though, is that they don’t allow efficient 3-point shooting or efficient shooting at the rim.

Defenses of the likes of the Indiana Pacers, Memphis Grizzlies, San Antonio Spurs, and Chicago Bulls are all built around stopping Moreyball style 3-and-rim scoring. The result is that a team’s playoffs and eventual finals success is highly dependent on a team’s ability to be flexible enough to adjust their offense away from only being able to score from 3 and at the rim.

In short, there is, eventually, a need for “shot creators,” who can make a midrange jumper or a shot at the rim into a more efficient attempt on championship bound teams.

Consider this fairly simple example: on a pick-and-roll play between an elite offense and an elite defense, a defense has (more or less) three functional options when defending: they have to leave either a midrange jumper, a 3-pointer, or a shot at the rim with minimal defensive coverage.

Generally, a shot is left open on the pick-and-roll due to the defenses either having to send an extra defender to help the play, because they have to hedge the to protect from an off-the-dribble shot, or because the defender has to go under the screen.

Per Synergy Sports, these plays can account for 40 or more possessions per game, and so account for almost half of a game in many instances. Lots of plays will not be executed as perfectly on either end, though, as this thought experiment will imply, and I am aware of that.

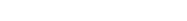

This play can be visualized as such:

Here, the first decision is the defense’s on what to allow open when defending the pick-and-roll. The second one is the shot that the offense chooses to take.

The numbers are the expected values of the given shot¹, by an average player, that is either open or contested, depending on the circumstance. The numbers by the defense’s options are the sums of the expected values of the shots that the offense could take.

The obvious option for the defense, then, on average, is to allow the midrange jumper (typically by having the ball handler go over the screen and having the big man drop back, though there are other versions), because the sum of the expected values for that decision is much lower. We see that played out in how teams like the Bulls and Pacers defend.

So, given that the options become “contested 3,” “open midrange jumper,” and “contested shot at the rim,” the smartest option would be to take the open midrange jumper, because the expected value on that shot is higher than that of the others.

That said, any defense would be happy to concede only 91 points on 100 shots, making this slightly more tricky.

An offense, then, needs to be trying to force defenses into allowing open (or, at least, less contested) 3’s and shots at the rim. They can’t do that, however, without bending and contorting an elite defense more than that defense normally deems necessary.

This all leads back to my original point, that a team that’s looking to maximize its effectiveness against an elite defense needs a player who can convert the midrange looks that are given to him at a rate much higher than average, or until it’s a shot that the defense will no longer be willing to concede.

If a team can convert conceded midrange jumpers at an elite rate, defenses will have to put extra resources into defending midrange jumpers, allowing offenses to find more open 3-point shooters and get better shots at the rim.

In essence, in a vacuum, Moreyball’s focus on 3 pointers produces a better offense, but an offense that is limited to such shots can be stagnated by an elite defense.

An offense that features players who are elite at taking inefficient shots more efficiently both has increased production against an elite defense inherently, and also can operate under Moreyball principles more smoothly under pressure.

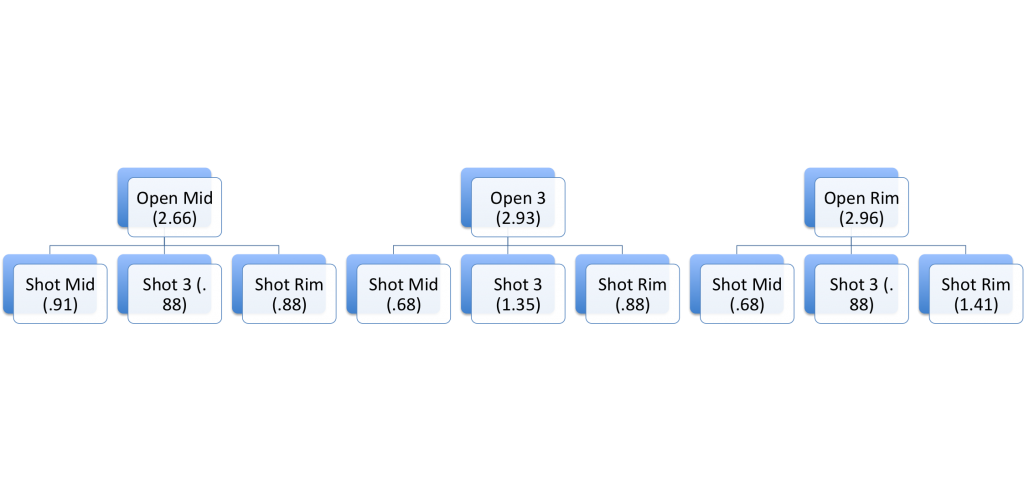

To illustrate this, lets look at the production of three different teams from last season: the Hawks, Rockets, and Trail Blazers. All three teams were built off of analytic principles, they were the top-3 teams in 3-point attempts per game. They also have all done so differently.

The Hawks have built their team around pure shooting, just total 3-point bombing from all 5 positions.

The Rockets are built on totally eliminating the midrange jumper, but unlike the Hawks, they have players capable of turning an inefficient shot (say, at the rim) into an efficient one, in James Harden and Dwight Howard.

The Blazers, by contrast, are built around their superstar, LaMarcus Aldridge, who took more midrange jumpers last season than the entire Rockets team, though the Blazers use Aldridge to open up more efficient shots than the rest of the team.

To illustrate how these different methods of building affect a team’s performance against the best defenses, I put together a chart of each team’s 3-point attempts per game, their offensive efficiency per 100 possessions, their Expected Points Per Shot (XPPS) profile — which details the efficiency of a team’s shot selection — and then each team’s offensive efficiency against the best five defenses in the league last season.

The margin isn’t huge, but it’s also distinct. Having players to vary the offense and force defenses to stretch themselves farther than they can and still execute perfectly is necessary to maximize an offense’s effectiveness against defensively elite teams.

The point here isn’t that building a team around 3-point shooting and shooting at the rim is a bad idea. The point is that maximizing the effectiveness of three-point shooting and shooting at the rim necessitates that there be a weapon that can break down a defense that’s already optimized to stopping that particular type of offense.

*****

¹ The expected values in the decision tree were calculated under the assumption that an “open” shot included 3 feet of open space or more, and using league averages from each distance given either “open,” or “contested.”

Contested shots at the rim were calculated by adding the expected value of a contested shot at the rim, the value of a lightly contested shot in the paint, and the value of free throws, all weighted by the odds of each occurring on a drive to the basket on a pick and roll, on average, per Synergy.